Felicity’s Blog

Introduction

Welcome to my blog for the research project that is Emergence! A little like a process diary, it is a behind-the-scenes, auto-ethnographic set of reflections on just some of the many undertakings that have been involved in the course of this research since it began in January 2023. These oscillate from critical reflection on forums and events I have attended, commentary on readings and creative works that matter to this research and to me, the deeply subjective thoughts that accompany any creative interaction, and some photos captured in secret from within the audience at contemporary opera events which hopefully won’t offend/break the law. I am indulging in this in hope that the informal record of a researcher’s journey might be helpful in ways that the formal outputs we produce are not, that my random musings on trains, after shows late at night, or in order to gather my thoughts between demanding workshop days might put a human face, a pulsing heart to this beautiful conundrum we call artistic research.

But first, some lists…

Opera/music-theater works I attended (in-person), 2023:

Listed by composer (more on this later):

Mary Finsterer, Antarctica. Sydney Chamber Opera, Asko Schönberg Ensemble. Sydney Festival, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

Lina Lapelytė, Sun and Sea. Sydney Festival, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

Du Yun: In Our Daughter’s Eyes. Protoype Festival, New York City/Lenape Land.

Gelsey Bell, mɔɹnɪŋ [morning//mourning]. Protoype Festival, New York City/Lenape Land.

Emma O’Halloran, Trade. Protoype Festival, New York City/Lenape Land.

Emma O’Halloran, Mary Motorhead. Protoype Festival, New York City/Lenape Land.

David Lang, Note to a Friend. Protoype Festival, New York City/Lenape Land.

Silvana Estrada, Marchita. Protoype Festival, New York City/Lenape Land.

Deborah Cheetham, Woven Song. Short Black Opera, Sydney Festival, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

Andrée Greenwell, The Three Marys. Sydney Opera House, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

Jennifer Walshe & Matthew Shlomowitz, Minor Characters. Darmstadt Festival, Darmstadt.

Kurt Weill, Aufstieg und fall der Stadt Mahagonny. Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam.

Bernard Foccroulle, Cassandra. La Monnaie de Munt, Brussels.

Symonds, Poulenc, Saariaho, Earth. Voice. Body. Sydney Chamber Opera, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

William Kentridge,* Sybil. Sydney Opera House, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

*not the composer

Opera/music-theater works I attended (in-person), 2024:

Christoph Willibald Glück, Orfeus and Eurydice. Opera Australia, Opera Queensland & Circa, Sydney Festival, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

Stephen Page,* Baleen Moondjan. Adelaide Festival, Adelaide/Kaurna Country.

Igor Stravinsky, The Nightingale and Other Fables. State Opera South Australia Chorus & Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, Adelaide Festival, Adelaide/Kaurna Country.

Kurt Weill, The Threepenny Opera. Berliner Ensemble, Adelaide Festival, Adelaide/Kaurna Country.

Wende, The Promise. Royal Court Theatre. Adelaide Festival, Adelaide/Kaurna Country.

Thomas Adès, The Exterminating Angel. Opéra de Paris, Bastille.

Sebastian Rivas, Otages. Opera National de Lyon, Lyon.

Ellen Reid, The Shell Trial. Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam.

Grey Filastine, Walid Ben Selim, Brent Arnold, Ali. La Monnaie | de Munt, Brussels.

Andrea Voets, For Real. O. Rotterdam.

King Sisters, Close to Harmony. O. Rotterdam.

Annelies Van Parys, Notwehr. O. Rotterdam.

Gregory Frateur, Nicolas Rombouts, Sjoerd Bruil, Memory Loss Concert. O. Rotterdam.

Het Geluid (Tamara Miller) & co-creators (Ted Hearne), Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Lucia Ronchetti, Searching for Zenobia. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Kai Kobayashi, Shall I Build a Dam?. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Nico Sauer, Rüber: A Traffic Opera. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Eve Georges & Jiro Yoshioka, nimmersatt. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Du Yun, Novoflot. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Yiran Zhao, Oblivia. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Mithatcan Öcal, Defect. Münchener Biennale, Munich.

Raphael Jacobs,* Quartier Est: Barre d’Immeuble IV. Opéra National de Paris, Bastille.

Peter Maxwell-Davies/György Kurtág, Songs and Fragments. Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

Claude Debussy, Pelléas et Mélisande. Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

William Kentridge,* The Great Yes, the Great No. Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

George Benjamin, Picture a Day Like This. Opéra Comique de Paris.

Kris Defoort, The Time of Our Singing. La Monnaie | de Munt, Brussels.

Clara Olivares, Les Sentinelles. Opéra de Bordeaux.

Images left to right (by Felicity Wilcox unless indicated): In our Daughter’s Eyes, Trade, mɔɹnɪŋ [morning//mourning], Mahagonny, Sybil, Antarctica

Images left to right (by Felicity Wilcox unless indicated): Quartier Est, The Shell Trial, Close to Harmony (photo O. website), Baleen Moondjan, Ali.

Above right- bottom to top: Searching for Zenobia, Shall I Build a Dam?, Picture a Day Like This, The Great Yes, the Great No.

Opera/music-theater works attended (in-person, so far) 2025:

Luke Di Somma, Siegfried and Roy: The Unauthorised Opera. Sydney Festival, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

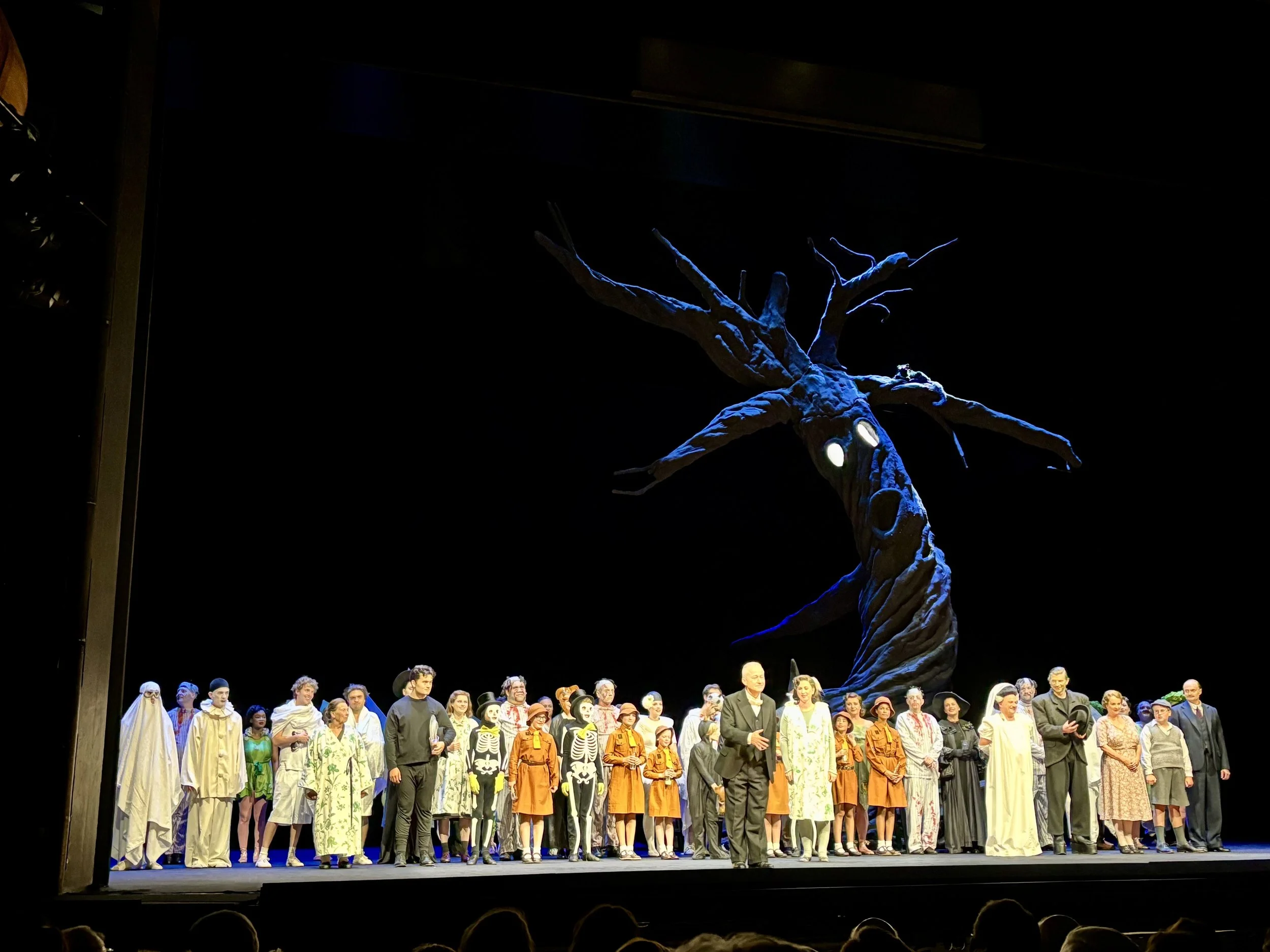

Kaija Saariaho, Innocence. Adelaide Festival, Adelaide/Kaurna Country.

Nico Mulhy, Aphrodite. Sydney Chamber Opera, Sydney/Gadigal Country.

Francesco Cavalli, La Calisto. Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

Sivan Eldar and Ganavya Doraiswamy, The Nine Jewelled Deer. Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

(After) Benjamin Britten, The Story of Billy Budd, Sailor. Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

Giuseppe Verdi, Falstaff. Glyndebourne.

Giacomo Puccini, La Bohème. Opéra National de Paris.

Modeste Moussorgski, Boris Godounov. Opéra de Lyon.

Images left to right (by Felicity Wilcox unless indicated): Innocence, Falstaff,

Blog Posts

(Click on a ‘+’ sign to open the post)

Thoughts on ‘Picture a Day Like This’ by Opéra Comique de Paris

-

Libretto: Martin Crimp

Score: George Benjamin

Opéra Comique de ParisThis work had beauty and craft. It did not move me…

And, it was another story about a woman written by two men.

Striking points:

no verse/chorus structures

no rhyming

no ‘songs’

there was a beautiful interplay between music and the texts. The instruments painted mood, colours, effects, shapes.- much word-painting, some of it clearly related to text, at other times more obtuse, perhaps a reflection of the composer’s stream of conscious. I liked these ones. The harp playing Matisse green was a favourite moment.

motif didn’t matter

it was thoroughly through-composed, like a story being read to us, but played and sung instead.

it floated largely out of discernible time

These are all good and timely things to have observed, and helpful.

Not that I aspire to write a work like this. For one, the libretto I am working with has song structures and rhymes, is inherently rhythmic. I need to work with the structures and language Alana has offered. I am also comfortable with more tonality and more repetition as befits my song writing work. I have seen these traits put to good use in other new opera pieces, and they can work.

And, I want our work to move people. I strongly believe after everything I’ve seen these last 20 months that opera that fails to move its audience misses the point.

And I’ve just realised why this one left me cold. It fundamentally missed this point:

hello! the woman had just LOST HER CHILD. Yet, no scene dealt with that. At no point were we invited to feel that loss, that relationship between mother and child. Instead the story focused on these weird tangential characters and the woman’s quest to find someone who was happy. I didn’t really even understand the ending. Whose button did she find? Was it supposed to be her child’s? I’m guessing so.

This work had lots to teach me (and remind me) around composition as craft, word painting, orchestration, freedom of the lines. But, I’m afraid for me it didn’t work. It was narrative opera and yet, the story, based in so much vulnerability and sadness, was hugely short-changed.

In opera, formal innovation is a plus, a bonus, but is not an end in itself. If that comes with emotional resonance you have won.

Opera or music theater?

-

Being from Australia, I had not come across the term ‘music theater’ until I spoke to German opera makers for this research in 2023. Until then, I would have conflated this term with ‘musical theatre’ (i.e. Hamilton, The Sound of Music and the like). But for Germans and many others, the word ‘opera’ apparently reeks of Wagner, high-art, the bourgeoisie, and all the attendant truckloads of baggage inherent with such associations. It indicates a form stuck in the past and dripping with gold. Colonial gold. They prefer the term ‘music theater’ - perhaps understandably. This term rather, reimagines not only the name of the genre ‘opera’, but the art form itself, to suggest a marraige of music with theatre in a more contemporary and egalitarian take on Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Composer/researcher Pia Palme explains music theater as: ‘composed musical space, or a space with music-not in the usual sense, but in the sense of sound, sounding bodies, performers and their relationship to the space’ (Schimana, Palme, Kogler, Lehmann 2022). From what I’ve observed over the last 15 months, music theater can be opulent, but more often it is lean, it can be long, but more often it is short, it can be 100% sung, but more often it incorporates speech, it can sound traditional, but more often it sounds experimental. Unlike ‘musical theatre,’ music theater is not populist, but rooted firmly in the realm of art music. To me, it feels like a revelation. It feels like home. I like the idea of shaking that tall, Wagnerian tree. Some works on my lists are straight-up operas; some are works of music theater; sometimes it’s not so clear and I suspect it doesn’t matter. None are musicals. This research is not about musicals. I‘m drawing the line. Orientation session done.

Schimana, Palme, Kogler, Lehmann. 2022. On the fragilities of music theater. In: Sounding Fragilities, I. Lehmann & P. Palme (eds.) Wolke Verlag, Hofheim. text goes here

The Composer as ‘auteur’

-

I am a composer. Moreover, I am a composer who has spent years working as a ‘gun-for-hire’ in film, television, radio, theatre and other collaborative contexts. I very much understand what it means to share creative space and have my overall contribution misunderstood or overlooked in the final reckoning when it comes to giving credit where it’s due. This means I find the tradition in opera to attribute an entire work, at least on the macro level, to the composer, let’s just say, problematic. On the other hand, I find it refreshing and liberating that I am finally working in a form that allows the composer to lead and to take up the pole position. So, what to do?

Of course, I am not the first composer to wrestle with such questions. Again, I turn to Palme, whose reflection on this aligns so closely with my own thoughts:

‘With larger projects it’s impossible to do everything- it’s impractical and time doesn’t allow it, not to mention that it would be boring... Of course, there’s a division of labor and responsibilities…And then there are collaborations…The question with collaborations is always: something specific has to be printed in the programs. …That’s the point where I don’t know how I should designate authorship…Because when it comes to the music, I am in fact the composer. The assignment of rights is difficult from a legal standpoint. How do you register a collective? Often the original idea is mine and then I produce the piece. I look for people to collaborate with, I start talking to artists and musicians - but the original concept was mine. Is that important, or isn’t it?…..I ask myself, half-consciously, why shouldn’t there be women who work and appear like Richard Wagner? Is that forbidden? Do I, as a woman, automatically have to fit my work into that of a collective? What authorship can I claim as a woman, or as a queer person? Can I take on a role like Wagner did? Am I allowed to? I pose the question: does the collective dissolve individual responsibility? Where is the individual responsibility in the collective? Or: what name am I making for myself as an artist? In what way am I present? What role do I play in the music business?’ (Schimana, Palme, Kogler, Lehmann 2022).

These are such great questions: particularly for women, gender diverse people, people of colour, other minorities. We have not been allowed to take up space as ‘auteurs’ and now that we finally (maybe) can, it is tempting to step up and square our shoulders in that space. Yet, there are ethical questions at large as well. In my proposal for the grant that has propelled this very project, I made an appeal for disruption of the canon that places the traditionally male auteurs in opera on a pedestal. I still firmly believe this disruption is needed, as much to let others in, as to see the canon with its clothes off: the reality is that in this space no one makes work on their own. No one ever has. Perhaps, if we are to make truly feminist opera, in the words of soprano and essayist Juliet Fraser, we first need to:

Kill the muse

Kill the diva

Kill the auteur

(Fraser 2023)

I’m going to take a slight liberty here, and say I think Juliet means ‘Kill the (idea of) muse, diva, auteur,’ as she would likely agree there’s been way too much killing - particularly of archetypal female figures- through the course of operatic history. I myself, am still working out what to do with all this. As a woman, it is a challenging proposition for me to take up the title of ‘auteur.’ There is something about this idea that fundamentally rankles and I shrink away from it. Call it conditioning, or call it seeing through patriarchal structures that I am not comfortable adopting. So perhaps the way through this mess is for me to accede to the pole position on the condition that the auteur myth be busted. So I want to start by acknowledging the contributions others make to my project in documenting it, all the while holding this new, powerful space I inhabit as ‘the composer’ of a new opera, and acknowledging the beautiful privilege of finally having earned my entitlement to it.

Fraser, J. 2023. Deconstructing the Diva: in praise of trailblazers, killjoys and hags. Presented at the Fourth International Conference on Women's Work in Music 2023, at Bangor University.

Schimana, Palme, Kogler, Lehmann. 2022. On the fragilities of music theater. In: Sounding Fragilities, I. Lehmann & P. Palme (eds.) Wolke Verlag, Hofheim.

Inclusion is an action

-

Reflection post development workshops with singers for Emergenc/y (Day 2):

The way we made room for the state of mind of participants changed activities. This is about accessibility. (Neurodiverse participant) X had to leave during the ‘quiet sounds’ jam because they didn’t know how the recorded sounds had been generated. They couldn’t see the source; this made them feel uncomfortable. This factors into considerations of sound design; that I must have sound sources visible, or at least traceable, perhaps with players visible, if we want neurodiverse audiences (and performers!) to engage.

Inclusivity is in action, not just words. I thought I was already being ‘inclusive’ by using improvisation and report data in my methodology. Turns out once that general framework is established, inclusion then becomes really nuanced. By accepting and embracing people’s contributions and perspectives you invite them into the whole process. This included performers leading relaxation exercises, suggesting layouts, set-up and lighting, deciding which direction they were facing as we workshopped a scene; it extended to everything about their involvement. Almost half of our performers are neurodiverse so it’s presenting all kinds of alternative angles on ideas, learning modes, sensitivities, abilities, approaches, endurances, tolerance levels, etc. I’m learning that genuine inclusion means adapting the process and the work itself to the circumstances, not taking for granted performers will necessarily do what I want in the ways I expect!

‘Sparks jumping’

-

Reflection post development workshops with singers for Emergenc/y:

When asked by Juliet Fraser to describe some advantages of composer-performer collaboration, Pia Palme responds: ‘the sense of sparks jumping over between artistic-minded individuals, a spark that can trigger something that reaches beyond what was there before, into some new terrain…Moreover, this experience seems to happen in a space outside of myself, yet connected to me- a “third space”?’ (Palme, in Fraser 2022).

I love this. Palme’s words perfectly describe the way I felt when we reached the end of the workshops - I was merely offering words, a phrase, and the soloists were just going wherever these prompts took them. At this point I felt like I was in a self-driving car. Definitely going where I wanted, but not necessarily on my terms or in the driver’s seat!

I experienced the dual act of ‘giving space and taking responsibility at the same time’ (ibid.) as the most natural urge, yet also found that walking this tightrope was the greatest challenge. It was the work; it was constant. It required vigilance and commitment, self-regulation. It was about creating a culture, paying attention to people, and also paying attention to the work. It felt profoundly feminist in that it was about care. Listening. Agility. Flexibility. Availability. All the things I have practiced as a mother and a teacher. Yet it was also about nuanced, engaged, high-level arts practice. Affirmingly, it felt like I was pulling together the disparate threads from my commercial work as music director running sessions, as concert composer mediating with performers on my scores, as a hired hand on the receiving end of others’ direction, and as an educator with a duty of care over people with diverse needs. It took all of me. All of my training and expertise to give space and simultaneously take responsibility. But it worked! Each performer went out of their to way acknowledge this and to thank me for the spaciousness and trust I created from the get-go. And that, I suspect, was why I got to sit back in that self-driving car by the end.

I think the routine I established of guided improvisation sessions followed by work on the notated ‘Calling’ compositions was also really effective and important. Because: a) it neutralised the dynamics between performers and put them all on equal footing, where in improvs much of what they offered was dictated by their confidence and/or experience; b) it reasserted my role as ‘composer’ and theirs as ‘performers’ whereas at other times these roles were not so clear or meaningful. Coming back to these traditional, clear boundaries allowed the other activities to be more porous; c) It gave the cast a glimpse of how it might feel to perform ‘my’ music, which appeared for the most part, to be a good experience for them! So, even as I was learning about the sound they made, they were learning about the sound I made. This interplay strengthened our mutual understanding of the process around and quality of each others’ work. I only hope we are allowed to continue to work in this way once the big fish start to bite.

Fraser, J. 2022. In the thick of it. Further reflections on the mess and the magic of collaborative partnerships. In: Sounding Fragilities, I. Lehmann & P. Palme (eds.) Wolke Verlag, Hofheim.

Thoughts on ‘feminist listening’

-

Some women’s* bodies are porous vessels. Even as I write, my insides are finding their way to the outside through uterine bleeding that no doctor has an answer for yet. I write and I bleed. I don’t know why this is happening and it makes me feel vulnerable – as bleeding during my fertile years always did. As the wayward trickle continues, I feel somehow undermined, leaky, fearful. My biologically female organs still communicate my inward vulnerability to the world even if silently and covertly.

We are porous vessels. During the workshops with singers that ran over 4 days, it was noted quietly on about day 3 that some people’s periods had synced up. It was also around the time we were all at our most vulnerable and really opening up to the process, the work, and to each other. It made me think about how our bodies were listening to each other: ‘listening with the body is also feminist’ (Palme 2017, p.23). In a way perhaps other bodies don’t, women’s* bodies listen, open, offer up, absorb. Through our very flesh, we listen. Perhaps this is why some say that feminist listening is about embodiment.

Christina Fischer-Lessiak writes, ‘the feminist ear and feminist listening are active and challenge an imagined normative or patriarchal listening’ (2022, p.94). The latter, suggests Jennifer Stoever, is ‘socially constructed… and normalizes the aural tastes and standards of white elite masculinity as the singular way to interpret sonic information’ (Stoever 2016, p.13). Hildegard Westerkamp suggests that ‘there might be differences between how the feminine in us processes what we hear and how the masculine in us does it’ (1995), a framing that leaves the question of gender open, allowing for men and other genders to also engage in feminist listening. I think it is important to make this distinction; saying that all women practice feminist listening or even unconsciously listen in the same way is as ludicrous as asserting there is a ‘women’s music.’ Not the point.

And again, to Palme: ‘Listening inward and outward in the same way and involving one’s own mind in the process, that I define as feminist (my emphasis)’ (Palme in Fischer-Lessiak 2022, p. 92). I like the idea of taking responsibility for communication, checking within and without as one listens consciously, and I would agree this is a predominantly feminine trait, honed by living within societal structures that place us in caring roles, within tight-knit collectives of solidarity, and on the receiving end of power: ‘feminist listening allows awareness of power structures by being reflexive of one’s own listening practice…Without anyone really listening, communication fails’ (Fischer-Lessiak 2022, p. 96-7). We are expert listeners because we have had to be.

There is no single way to define feminist listening, but what I am interested in exploring through Emergenc/y and other work I make, is precisely to challenge normative listening and influence how we experience the world and ourselves (ibid., p. 97). A key goal of this work is to ask audiences to take responsibility for listening ‘as an active and creative process [that] might serve to undermine certain hierarchies of language and voice… and create a public realm where a plurality of voices, faces, and languages can be heard and seen and spoken’ (Bickford 1996, p.129).

And while, as ever, I am down with acknowledging the legacy I inherit from my elders, and the shoulders on which I stand, I also want to move the conversation on. I prefer the term ‘inclusive listening’ because I know a number of men and gender diverse folk who practice feminist listening – at least as musicians. I believe we all move forward together, with less resistance if we deemphasise gendered ownership over new ways to listen. As Pauline Oliveros states: ‘inclusive listening is impartial, open and receiving, and employs global attention’ (Oliveros 2005, p.15). And if there is any edict at all guiding my thoughts for the sound world for Emergenc/y, it might just be this: ‘Inclusive [listening] means also to listen closely to silences, background noises, the concealed, and unsaid’ (Palme in Fischer-Lessiak 2022, p. 92). Let’s listen for the unexpected - it might just be interesting!

*To be clear: I mean all people with biologically female bodies, not all women and not only women (but this doesn’t flow quite so well in prose). Thank you for indulging me and letting me write in my own voice, from my experience.

Bickford, S. 1996. The dissonance of democracy,: listening, conflict, and citizenship. New York: Cornell University Press.

Fischer-Lessiak, C. 2022. How feminism matters - an exploration of listening. In: Sounding Fragilities, I. Lehmann & P. Palme (eds.) Wolke Verlag, Hofheim.

Oliveros, P. 2005. Deep listening: a composer’s sound practice. New York: iUniverse.

Stoever, J. L. 2016. The sonic color line: race & the cultural politics of listening. New York: New York University Press.

Westerkamp, H. 1995: Listening to the Listening. International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA), Montreal, 1995.

On the ecology of quiet sounds

-

‘Inclusive [listening] means also to listen closely to silences, background noises, the concealed, and unsaid’ (Palme in Fischer-Lessiak 2022, p. 92).

Let’s start where we left off yesterday, with today’s thoughts on this beautiful idea. For some reason I have become obsessed with exploring very quiet sounds. This probably intensified during the pandemic when we were all stuck at home and the world was quieter. It extends through to my fascination with birdcalls and other small, delicate sounds of nature I have increasingly observed since moving to an extraordinary wild environment 14 years ago. Always the die-hard urbanite, I had hitherto disregarded such sounds as whimsy, trivial, irrelevant. I had taken them for granted. Now I have come to respect, understand and pay attention to them as essential to the environment I rely upon. I observe the tiny sounds, sometimes the raucous ones, of my fellow creatures as signatures that mark the weather, the time of day, the presence of others – family, mate, or predator - sounds of their feeding and sleeping, playing and breeding; these sounds have now become integral to my daily life. I have also become aware that these other beings listen to me; the cricket that stops chirping as I pass, the frog that silences its pulse when I speak, the snake that writhes away from my footfall, the sulphur-crested cockatoos that cock their heads at my conversation and respond in a cadence that mirrors it. This has allowed me to understand sound as something which passes through me and listening as, ‘an ecology in which we are not only listening, but listened to’ (Robinson 2020, p.98). I turn again to acoustic ecologist and soundscape composer Hildegard Westerkamp in my attempt to articulate the new directions this is taking my practice in:

‘We are the ones that make listening and working with sound and music our profession. It is therefore a logical extension that we would also be concerned about the ecological health of our acoustic environment and all living beings within. If we — who are specialists in listening and sound-making — are not concerned about the acoustic environment, then who will be? …Why then should composers and musicians not make it their calling to use their special knowledge and education to listen to the world from the ecological perspective?’ (Westerkamp 2002).

Composers have been co-constructing the idea of an ecology of music since the 1960s. Important practitioners and thinkers in this area include William Kay Archer, John Cage, R. Murray Schafer, Annea Lockwood, Pauline Oliveros, and of course, Westerkamp (Palme 2002, p. 50-1). Pia Palme says that ecology influences the contextual parameters of music making: ‘the content, the structure, and form – the aesthetics – of composing as well’ (ibid., p. 51). This is increasingly true of my own compositional and improvisational practice, evident in my works which directly examine ecological and environmental questions (e.g. Tipping Point 2021; Currawong Call 2021; Call and (a) Response 2022). However, in my view, such an ‘ecological perspective’ should not only include, but might also stretch beyond, the realm of nature and other species with whom we share our planet to members of our own species who may be hidden from view, struggling to survive, silenced by the forces of our masculinised, militarised, industrial society and the structures of patriarchy. I feel we must attend to, to emphasise Westerkamp’s phrase: ‘the ecological health of our acoustic environment and all living beings within it’ (Westerkamp 2002). In other words: certain people, ideas, and voices that we don’t usually get to hear above the din. I have developed a determination to seek them out in Emergenc/y and other works I am making in this phase of my career. Thus, I am interested in invoking processes through these works that ask for a different quality of listening to music and sound, to each other, and to ourselves, making the act of creating work a ‘journey that circumscribes the relationship, the conversation between composer and sound sources’ (ibid.) – and that invites the audience to enter into the act of curious listening too.

A conceptual underpinning of Emergenc/y is to consider the question of gender from different angles. I myself have often experienced objectification due to my gender, or trivialisation, or worse. On such occasions it felt absurd that here I was, presenting myself in my entirety as a human being, while the other person was only seeing me for my gender and judging me according to their own gendered prejudices. This was a thread echoed by respondents across the recent study I conducted with over 200 female and gender diverse music creators resulting in the Women and Minority Genders in Music report (Wilcox & Shannon 2023). Thus, I felt that in Emergenc/y, we might explore ways of going past the external physical features of a person to investigate their internal corporeal reality as a framing for some of the practice-based research.

I asked performers (see Emergenc/y page on this website for performer bios) to investigate the internal structures of their instruments, as well as any very quiet sounds they might yield through radical extended techniques and preparations. Composers such as John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, Cor Fuhler, Aphex Twin, Liza Lim, Malin Bång, and many improvisers such as Magda Mayas, Laura Altman, Aviva Endean, Jim Denley have explored such ideas. They have similarly been a feature of the exploratory practice I investigate with my collaborators John Encarnaçao and Lloyd Swanton in our improvising project, W.E.S.T. (see Cooke & Wilcox 2022). But such ultra-quiet sounds are not traditionally considered suitable within an operatic context – if for no other reason than that they would simply not be audible.

Also as a metaphor for ‘amplifying the voices’ of the marginalised; I was interested in recording these super quiet, internal sounds in optimal conditions, and then during the performance magnifying them through amplification. This even led to enquiries about using the anechoic studios at my university for recording with a near-silent noise floor (an idea that hit a logistical stumbling block). I did however engage my sound designer, Bob Scott, to make recordings of the super quiet sounds we had together with the performers identified as being of interest to the project, using hyper-sensitive mics, a sound-proof room and professional speakers to accurately gauge the result. These recordings were made at a sample rate of 96k, in 7.1, and aside from capturing performances of mostly very quiet, isolated sounds resulting from radical extended techniques and preparations, they also captured free improvisations by the performers using these techniques (and others) that lasted several minutes. These improvisations are precious artefacts, in that they range across techniques in ways particular to each improviser, bringing the inner and outer dimensions of both performer and their instrument together ‘and in this totality the entire ecosystem can be heard’ (Palme 2022, p.51). I am now in the process of devising ways to include them in the final work. Listen to this space!

Cooke, G. & Wilcox, F. 2022. Audiovisual Gesture and Spectromorphology: the Invalid Data W.E.S.T. project. International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media. Vol. 18(1). London: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794713.2022.2101317Palme, P. 2022. Composing futures. Activism and ecology in contemporary music. In: Sounding Fragilities, I. Lehmann & P. Palme (eds.) Wolke Verlag, Hofheim.

Robinson, D. 2020. Hungry Listening. Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Westerkamp, H. 2002. Linking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic Ecology. Organized Sound, Volume 7, Number 1, 2002.

Wilcox, F. & Shannon, B. 2023. Women and Minority Genders in Music, University of Technology Sydney: Sydney. https://www.wmgmreport.com

On inclusive listening and working cross-culturally

-

‘The conceptual involvement of everyone is an integral part of my work…there are no majority decisions…There are discussions, different thoughts, but the character of an artistic work must be precise, clear’ (Bianchi, in Fraser 2022, p.256-7).

For choreographer Paola Bianchi, rather than inclusive process muddying the final outcome, it hones the work. Bianchi is here speaking about creative teams and artists from different disciplines finding agreement through creative processes and her words are also true of the process I am bringing to Emergenc/y through development workshops, yet I would extend this idea to involving the perspectives of diverse people from minority backgrounds in the team, including First Nations artists.

My decision to cast two First Nations singers in my team of 5 soloists was taken in line with my intersectional feminist approach to making this work, and my determination to implement inclusive practice where possible from the start. The two First Nations practitioners involved in Emergenc/y, Sonya Holowell and Nicole Smede, are highly skilled improvisers, which is a key requirement of my cast, both also read notation, also a fundamental requirement, as well as having voices I am inspired to write for. Although from very different backgrounds culturally and musically, I feel we share a curiosity about music making and an understanding of each others’ sound worlds. These factors had to be true of all my soloists. The fact these two talented women are also First Nations was yet another compelling reason to invite them to develop the work with me. For those of us making Australian work on any theme, I believe it is incumbent on us all to invite a First Nations perspective into our work as this is what the idea of a ‘voice’ is all about. The referendum might have failed, but we can all bring the idea of ‘voice’ into our practice.

British essayist and soprano Juliet Fraser writes that ‘the purpose of collaboration is to explore a new process of making and the hope is the results themselves somehow make a new proposition’ (Fraser 2022, p.257). As I had hoped, but not in ways I had necessarily expected, First Nations participation in Emergenc/y has already shaped its development in many ways.Fraser, J. 2022. In the thick of it. Further reflections on the mess and the magic of collaborative partnerships. In: Sounding Fragilities, I. Lehmann & P. Palme (eds.) Wolke Verlag, Hofheim.

Review of ‘Mahagonny’ by Dutch National opera

-

(Warning- this post contains content that might trigger some readers)

Date of performance: Sept 2023

Libretto: Brecht

Score: Weill

Director: Ivo van Hove

Musical Direction/Conductor: Markus Stenz

Dramaturgy: Koen Tachelet

Video: Tal Yarden

This opera by an all-male creative team did nothing to refresh gendered tropes that exist in traditional works. While it supposedly shines a mirror to contemporary society, it does nothing to question the ways in which women and gender diverse people have been traditionally cast as the property of men; in fact it works very much to reinforce those tropes. The casting included a number of POC, including Lauren Michelle in the lead role of Jenny, which was a coup, and in this regard the company’s diversity cred was on show. But that felt a little like box-ticking, when the video material only succeeded in fulfilling racist and sexist stereotypes through its proximity to porn-lite; close ups of sex workers (black and white) provocatively acting out (to their male clients); the audience was invited in, but only if they were, or could imagine being men, because I am here to tell you no sex worker has never/would ever behave towards me in that way.Moreover the close-up video might have been used to balance such superficial stereotyping, to register the deeper internal realities of these complex characters. To me this would have been a much more interesting use of video - however such ‘internal’ moments were exclusively reserved for the lead character Jimmy, who carries the existential thread of the plot and who, unsurprisingly for a work written by two men in the 1920-30s, is the man around which all the action revolves. The Director came close to portraying his leading female characters with similar nuance when he lingered on Evelyn Herlitzius (Widow Begbick) for a long close up; the camera at times flirted in close up with Jenny too, but such close ups on her were preoccupied with presenting a sexualised image. The director might have drawn us into a deeper dialogue with Jenny’s private, inner world through a more neutral (less voyeuristic) use of the camera and more nuanced directorial guidance of Michelle’s performance.

The use of video too often felt gimmicky- as though the director had his newest party trick on show. The split focus of trying to read surtitles, watch the action on stage, keep track of the handheld, fast panning video on the screen, watch the orchestra and conductor in the pit, and listen to the music was just sensory overload- with way too much visual focus and busy-ness for my taste. I liked the increased intimacy the camera afforded but felt it could have been used much more sparingly and judiciously to amplify the inner worlds of characters (as with Thomalla’s Dark Spring or Foccroulle ’s Cassandra), rather than create more chaos, which seemed to be the director’s intention all too often.

The real breakdown in my engagement with the directorial approach towards the video (and the whole show) occurred in the second half, when we were shown a young woman (presumably a sex worker) stripping off her clothes via the big screen. Her strip tease to full nudity is accompanied by loud cheers from the male singers on stage who are watching. Once she has stripped we are given free reign to observe her naked body for a while, as though the director wants us to enter into the eyes of the men who are hoping to sample her wares. At this point the male gaze so endemic to traditional opera asserted itself with force. It is as if the director had forgotten the thousands of women in the ‘room’; we in the audience are literally being presented the work through a 100% male gaze. Then the whole sequence went to the next level when the director chose to use green screen to present the young men on stage thrusting at a virtual set of buttocks, pants down and shirts off, one after the other, while the young woman (presumably somewhere backstage in front of a camera) leant forwards, breasts hanging, buttocks raised, to mime being fucked from behind. This sequence went on for an entire song, through at least 5 minutes and probably about 10 men, and I found it disturbing. Not due to the use of nudity or the depiction of sexual contact but due to its intense, resolute and unapologetic objectification of the young woman, who was the only one to be shown fully naked, who looked bored and miserable, and reminded me of the many such women one sees in porn videos. It was awful. Made worse and taken to a triggering level when the men united in cheering each other on towards the end of the scene, collectively looking on as one of their number virtually fucked the bent-over woman. I don’t care if it wasn’t real; big deal that it used green screen to show sex in a live production; it still felt like an unnecessary violation that reinforced the long list of problematic gendered tropes in traditional opera in a symbolic sense. It wasn’t novel; in fact it wasn’t clever at all. It was completely gratuitous and showed conservative sexist patriarchal values in full swing. So much for revolutionary new opera.

If this production really wanted to question contemporary society (as it claims to wish to do), I would suggest rather than stereo-typecasting of female and femme-male ‘whores’ (in the classic sense of the word) and forcing the audience to endure grossly overblown, close up, and long durational sex with a female nude as passive receiver – it might reverse the roles and use green screen to instead show the men full frontal, naked with dick and balls dangling, taking it up the arse with the woman in control, fully clothed and wielding a strap on. Flip the script please. That would have better suited my - and no doubt the other women and queer people in the room’s - taste more.

A final word about the music. It was great. Respect to the conductor. The orchestra was tight and subtle, and the final number worked like a juggernaut, meandering through tempi, driven by the bass section and percussion with a force that was so compelling I found my eyes riveted to their performance. The young men playing their basses were clearly enjoying themselves immensely, putting their whole bodies into it, resembling a rock band more than a pit orchestra at the opera. Watching them reminded me why I love music and why I love watching others playing it and playing it with others, including men. There is no doubt that watching the masculine alive in men is a beautiful thing, but does articulating this power have to come at the expense of others? I think we should be aiming to achieve works that feel OK for everyone to be a part of. If this production had shown women also in their power, women rocking out on stage, beautiful and in control and powerful in their destinies (qualities that Brecht has actually written into his character Jenny), happy and strong- even if there had been one such moment, I would have felt better about it. Instead, the women and gender diverse people were afraid, defensive, wheedling, small, cowering, subjugated, conniving, at best, simply cool – but always acting out in relation to the men they were orbiting.While we might expect nothing more from a work premiered in 1930, I do expect more from a Director making work for the stage in 2023. Next time, at the very least, make her a woman.

Review of ‘Cassandra’ by La Monnaie de Munt

-

Date of performance: 10 sept 2023

Score: Bernard Foccroulle

Libretto: Matthew Jocelyn

Musical Direction/Conductor: Kazushi Ono

Direction/Video Design: Marie-Eve Signeyrole

A narrative on climate change, riffing on the Greek legend of Cassandra who predicted the fall of Troy, where Sandra (Jessica Niles), a modern-day climate scientist, broadcasts what she knows about the fall of civilisation. The director also being a cinematographer (cinéaste) made for rich and clever use of images. There were many beautiful sequences conceived from a strongly visual foundation; bees were suggested by dancing particles; and there was actual projected infrared footage of bees in the hive. When the handheld camera followed singers around in the opening sequence I was bracing myself for another chaotic work that split focus between on-stage and on-screen, but this was only the case at the start, and thereafter it calmed down. If anything, it was a little bizarre that the hand-held technique only appeared once and was not returned to.

Other video use that worked well was of a slow-motion Sandra seen floating from underwater through oceans of melted ice, projected cranes in flight; these sequences had a hypnotic effect. The massive cube at the centre of the stage was a surface on which to project; it variously became an iceberg, a beehive. The most poetic scene showed Cassandra (Katarina Bradić) dancing with swirling particles projected onto the cube as it turned, with electric violins imitating buzzing. Curtains were thrown down from the ceiling and left hanging, delineating dissolving shapes that suggested icebergs calving. Use of light and shade was beautifully conceived and quite stunning visually; deep Antarctic blues, black and white and monochrome colour design dominated. Clearly, Signeyrole is a Director for whom visual language is a focus.

Musically, the work was interesting. I loved the use of the hidden choir who sang hymn-like and subdued from behind the set, like an omni-presence, an unseen Greek chorus, until at the very end they finally appeared in the theatre doorways singing at us from close proximity. Actors were planted among the audience, simulating spectators at Sandra’s speaking engagements; these devices broke the 4th wall and activated the dead and dark audience space in a fun way that felt quite natural and easy to accept. There were some awkward moments where banal conversational text was set to melismatic music that required highly-produced singing and I felt a little confused as to why sprechstimme wasn’t employed for such text given it was used on other occasions. Perhaps it’s because I don’t know his music yet, but I didn’t quite ‘get’ Bernard Fouccrolle’s musical language. It had moments of largesse, becoming expansive and immersive when it really pushed into high drama, but it didn’t have a clear character that I could pin down. ‘Epic’ ? but not like a Wagner, or a Saariaho. Aptly sweeping given the theme and it pulled us in and under when it mattered. The passages that I think were making an attempt at being humorous, involving percussion, woodblocks and quirky violin writing fell a little short- maybe because of the band not being quite tight enough.

The feeling I had when Cassandra ended was almost opposite to the frustration and annoyance I felt at the end of Mahoganny. While two white men of a certain age got up as composer and librettist to receive the highest applause at the end of each production, the sight of Foccroulle and Jocelyn humbly taking their bows brought tears to my eyes. Here were two oldish white men who had used their power and talent to get behind an issue that affects the young and vulnerable and who (it would appear intentionally) centred women in the telling of that story. While it would have been rewarding and appropriate to have seen even one of these two roles given to a woman by the commissioners, at least these two dudes gave authentic voice to people who did not look like them through this opera, and interrogated society in a genuine and deeply sincere way. However, I suspect it was Marie-Eve Signeyrole as Director who was the one who actually brought all the moving parts of this ambitious jigsaw together and who deserves the highest praise for the way she layered imagery, words and music to powerful effect.